A Brief History of the Disney Title Card Opening Sequences

Do you remember snuggling into bed as a child with your favourite storybook? The feeling of excitement to hear the story again even if you’ve heard it a million times, the joy it brings right before falling asleep. The power of a storybook has not dwindled over decades, even centuries, and fairytales are often a favourite of children all around the world. Fairytales have been adapted over hundreds of years, with Disney’s versions becoming the foundation for today’s retellings. This feeling of opening up a fairytale book is the feeling Walt wanted to emulate with the beginnings of his early movies. Snow White, Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty even opened with real books that are held in the Disney Archives. With this concept in mind and the early pattern of having opening credits rather than closing credits, the Disney title card sequences of some of the studio’s first movies are pieces of artwork. Let’s take a look at the history of the Disney title card/opening credit sequences.

Opening Credits Versus Closing Credits

Before we talk about the history of Disney opening sequences, we must go all the way back to the beginning when this concept was first used. According to Patrick Willems, the very first time any kind of opening title card or credit was done was in 1897 by Thomas Edison, and it was simply a “copyright by T. A. Edison” message to avoid piracy. Then, 1908’s Broncho Billy became the first film to credit the actors on screen before the movie, on a simple black screen with text. This idea of text being integrated into film goes back to the days of Silent Film, which would also normally feature a title card to introduce the title of the film and be a clear beginning point of the story. Even as time progressed and movie quality was rising, the title sequence remained a static themed image with a group of the casts names all together, and the various crew members throughout. The purpose, just as it was with silent films, was to be a clear indication that the movie was starting. When movie theatres used to play cartoons between their films (just like the early Disney cartoons would be), the title card would be a way to differentiate the 2 stories. Once we hit the 1950s and 1960s, directors took more creative liberty with the opening titles, adding moving backgrounds, animation, or even overlaying the text over the beginning of the movie as it played. This continued to dwindle down overtime when more crew members were being credited through the 1970s and 1980s, until there were just too many people to note, so the credits were officially moved to the end of the film.

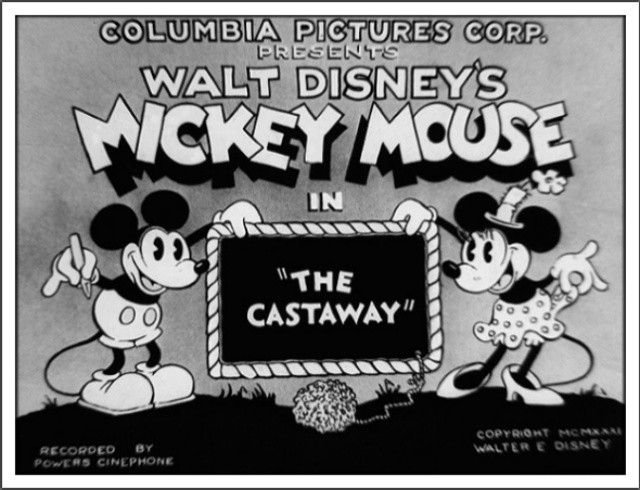

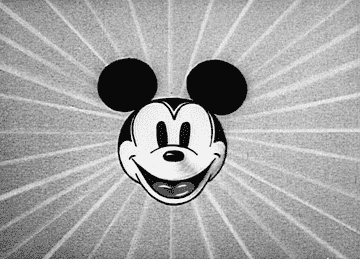

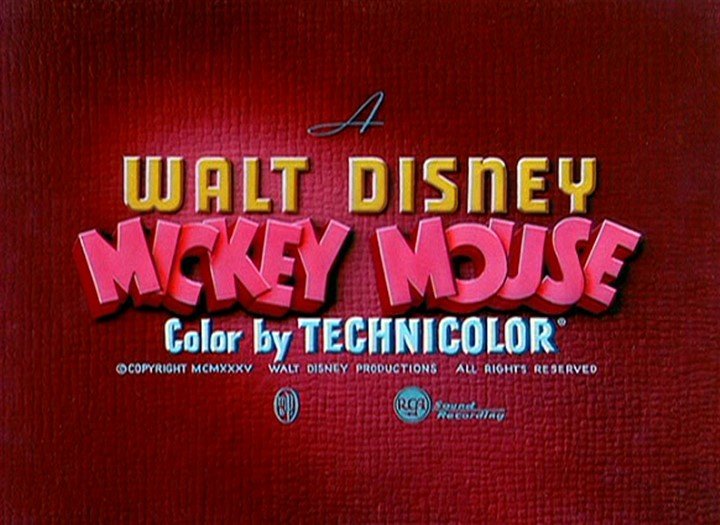

Mickey Mouse Cartoons Title Cards

Now that we know a bit more about how the opening credits changed through the various decades in the 20th century, we can dive deeper into how Disney followed those trends. Before the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Disney’s Mickey Mouse cartoons, Donald Duck cartoons and Silly Symphonies all had between 1 to 3 simple title cards that followed pretty much the same format with the exception of the title and sometimes the colours used. The first Mickey Mouse cartoons at the end of the 1920s had just the black and white “Disney Cartoons Presents A Mickey Mouse Sound Cartoon” and the title, with still images of Mickey and Minnie. In 1930, The Barnyard Concert got a new title card, with Mickey’s head beginning the show, then a newly designed second title card with a credit to Columbia Pictures Corporation. In 1935, when the Mickey Mouse cartoons finally got colour, the title cards were redesigned again to be even simpler, but with bright colours and the Mickey Mouse head still making an appearance. Behind these title cards, music always played, even right from the very first Mickey Mouse cartoon. These cartoons set the precedent for how they would design the opening sequence for Snow White.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (Uncredited Actors and Overtures)

The Snow White opening sequence begins with “A Walt Disney Feature Production”, the title of the movie, the necessary corporate credits and copyright messaging, a thank you message from Walt, and then it goes into the credits of the crew. Notice that the cast was not credited in this film, and it was a conscious decision by Walt. He didn’t want the illusion to be spoiled by the audience knowing who the voice actors and actresses were in real life, so they went uncredited, and even were not invited to the premiere. Despite this unfortunate circumstance, Snow White’s voice actress Adriana Caselotti was very proud of her work done on the film her entire life. This practice of not crediting actors continued for 6 years, until 1943’s Saludos Amigos. Watching the Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi and Dumbo credits, you won’t spot an actors name.

“My sincere appreciation to the members of my staff whose loyalty and creative endeavor made possible this production.”

The overture for Snow White, which plays in the background of the opening title cards, was written and composed by Frank Churchill, Larry Morey, Paul J. Smith, and Leigh Harline. It’s an instrumental compilation of the songs throughout the film, that was especially made for the beginning sequence. After the static title cards, the only unanimated part of the movie is shown, which is the opening of a Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs storybook.

Snow White opening title. Image from: http://andrewpointlessramblings.blogspot.com/2015/01/normal-0-false-false-false-en-us-ja-x.html

Snow White opening sequence. Image from: http://andrewpointlessramblings.blogspot.com/2015/01/normal-0-false-false-false-en-us-ja-x.html

The Pinocchio opening sequence followed the exact same format, except instead of a real book being opened, it’s Jiminy singing atop an animated Pinocchio storybook. The Dumbo and Bambi opening sequences experimented with a bit more creativity in the design of the title cards. Despite these small changes, the title cards remained relatively the same until they really started trying out new things in the mid-1940s.

Pinocchio opening sequence. Image from: https://bokoboww.wordpress.com/2012/09/30/pinocchio/

Dumbo title card. Image from: https://jessicarabbit.tumblr.com/post/115250366337/dumbo-opening-titles-and-credits-for-kim/amp

Make Mine Music (Animated Sequences)

Animation started playing a role in the opening sequences beginning with Make Mine Music in 1946. The opening begins with the actors names being lit up on what looks like the side of a tower as it pans downward. The title of the movie is on a Marquee, with music notes circling around it. After that, the static artwork makes a return. Little bits of animation like zooming and panning were scattered throughout opening credits for films after 1946. Disney did briefly go back to the storybook opening tradition with The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, The Sword in the Stone, The Jungle Book, Robin Hood, and the Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh.

Make Mine Music title card. Image from: https://forum.blu-ray.com/showpost.php?p=19508462&postcount=217

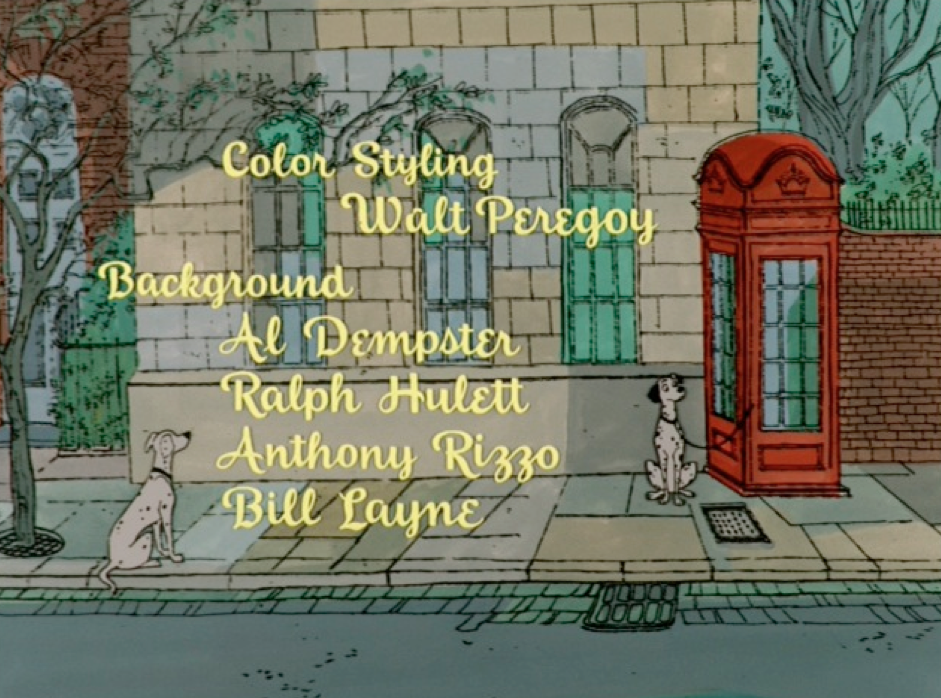

One Hundred and One Dalmatians made major strides in the Disney opening sequence progression and in opening sequence history in general. It had a fully animated, over 3-minute long introduction with exciting transitions, creativity with using the spots of a dalmatian, characters spread throughout it, and beautifully drawn backgrounds of London. This choice of going in a whole new direction reflected the film industry’s take on opening credits, and the hope to get audiences excited again after the flop that was Sleeping Beauty at the time. 1970’s The Aristocats attempted to do a similar thing as One Hundred and One Dalmatians but in a cheaper and faster way, by overlaying sketches of the characters interacting over simple coloured backgrounds. Robin Hood, 3 years later, would have higher quality animation of the characters in the film.

The Jungle Book (A Hybrid of Images and Animation)

The Jungle Book was another special one that stands out due to it’s unique format and incredible artwork. It was a hybrid between the static images from the classics and the use of animation that was emerging. It didn’t feature any characters, but rather backgrounds and scenes to be able to bring the audience to the setting the story was about to take place in. They used a depth-of-field camera to create the panning effect, having the elements closest to you appear blurry, and the things farther away seem more clear.

The Jungle Book opening credits. Image from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7iwb_YhlqIo

The Fox and the Hound (Ending Credits versus Opening Credits)

The Fox and the Hound in 1981 would start a whole new era of opening sequences that take you straight into the film, with the cast and crew credits overlayed on top of the first scene. The actors went back to being uncredited in the beginning, but rather were moved to the end to make the opening less extensive. This change came at the time noted above, in the 70s and 80s, end credits became a thing of the future. This format continued on until the early 2000s, when dedicated sequences were no longer being made just for the beginning.

Lilo and Stitch (The Final Opening Sequence)

Lilo and Stitch was the final Disney movie with a dedicated opening sequence, simply to introduce you to the type of girl Lilo is before the story begins. She’s the type to document her life, spend time with animals, and be late for her hula classes. Since 2002, there hasn’t been an opening that has been that long or very “disconnected” from the beginning of the story.

Lilo and Stitch opening sequence. Image from: https://www.polygon.com/features/22675483/lilo-and-stitch-disney-animation-chris-sanders-dean-deblois

Reference list:

http://gwenckatz.com/2014/10/10/a-history-of-disney-title-sequences/

https://disney.fandom.com/wiki/Storybook_opening

https://d23.com/these-12-disney-films-are-real-page-turners/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ha-ULMYHAFU&list=PLMnzu2VXBDJ4N55CEomiZ37I8eNayY7iO&index=1

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rPcWgLtzLC0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4FvMCg_SIqw&list=PLJO86QnVmoQgLDkQoslL7splUjLlJdJeM&index=64

https://www.thewrap.com/when-did-opening-credits-turn-closing-credits-movies-37062/